One of the most unifying things about being a Breastie, whether that be a major surgery to prevent a future of breast cancer, going through treatment, living with stage 4, or losing a loved one to the disease, is that the majority of us have gone through some degree of trauma.

The word trauma can be difficult for some people to get behind — it’s often an uncomfortable term — but calling it such can be a therapeutic act. It gives us the opportunity to view our experience without rose colored glasses, giving us the permission to heal as we navigate our changing relationship with ourselves and our priorities in life.

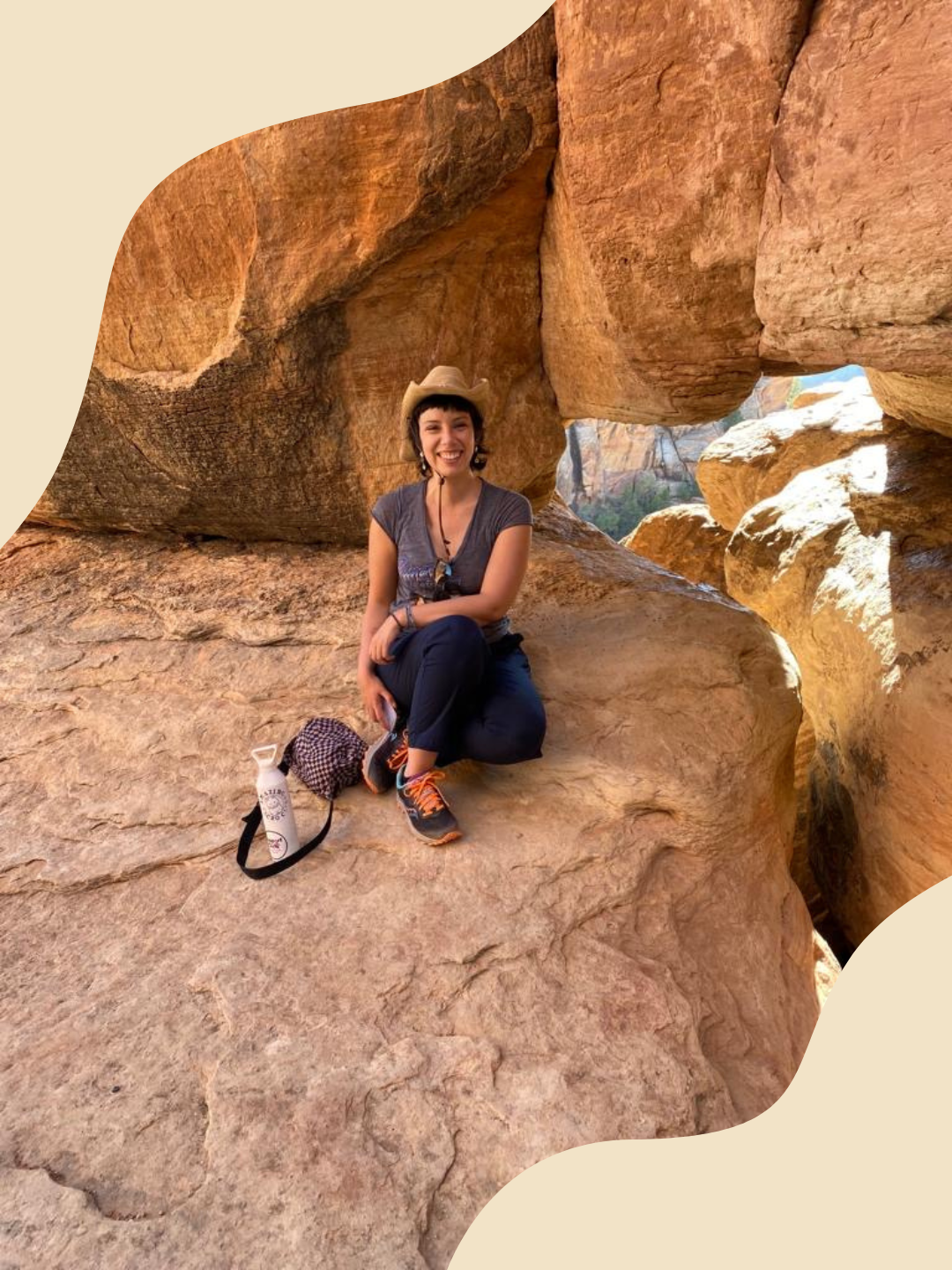

I have always been interested in mental health and the importance of it, in part in response to losing my mother to breast cancer at a young age. It was three months before I graduated high school in 2008, and it happened fast. According to the doctors, she was still in remission, so the level of shock to me and my family experienced was high, and the grief was tremendously heavy.

At the time, it truly felt as though I would never be able to continue living with any sense of joy or purpose, humor or happiness. The six months after my mom died are a blur to me now, with a lot of missing memories due to the shock.

More Loss and Complicated Grief

Cancer has always followed my family. Not only have I lost my mom to cancer, but my siblings and I also lost both my eldest brother and my father to the disease, within three weeks of each other, in June 2018.

Yes, you read that correctly. By the age of 27, I had lost both of my parents and my eldest brother to cancer. Little did I know that I would go through a breast cancer diagnosis myself, the following year. I thought I knew the depths of grief before, but this was a whole new beast.

“Complicated grief,” as they call it in the literature – when more than one death occurs, compounding, complicating, and extending the process of grieving (1).

It’s not a common phenomena from a diagnostic standpoint, but I would wager a lot of people might resonate with the term. Grief is complicated. Loss, of any kind, shatters our assumptions about the future.

How The Experience of Losing My Mom Informed How I Navigated More Trauma

What helped me during these dark periods, was that I was able to recall the emotions and thoughts of when I lost my mom. I remembered the profound feeling of hopelessness when we lost her, and the implicit question of, “will I ever feel happiness again?” that came in the wake of her death.

And yet despite these deep feelings of loss, I was able to find joy and a sense of normalcy and peace eventually. It took a long time, but I was able to get to where the grief about my mom was still present, but the sting was less intense.

As we faced the imminent loss of my dad and brother, I reminded myself of this fact: “I have felt these feelings of hopelessness before, and I was able to find joy in the end. So, I can, and I will find joy again. I know I have this capacity, because I have gone through this before.”

This thought brought me strength, as it reminded me of the innate capacity to heal that we all possess. Similar mantras were used between me and my remaining siblings: phrases like “this too shall pass," and “we are all in this together”.

Post-Traumatic Growth in the Wake of Loss

When my siblings and I were care-taking my brother and dad in hospice, I began reading Viktor Frankl’s work. I felt quite isolated with my story, so I started to read about people that had gone through tremendous levels of loss and trauma and yet had still found hope. What was different about these people? Frankl lost his entire family during the Holocaust, and yet he went on to help others find purpose in their lives, laying the foundation for existential therapy and logotherapy.

If you haven’t read his book, “Man’s Search for Meaning,” I highly recommend it. I was fascinated with the human potential his story demonstrated, and it prompted me to pursue a long-standing goal of mine – to become a clinical counselor, specializing in trauma and bereavement support.

A lot of us Breasties likely have symptoms of PTSD. I say symptoms, because really, PTSD isn’t a term that should be self-diagnosed. As well, some individuals resist the idea of taking on a standardized medical diagnosis, rejecting the idea entirely. Both are valid.

PTSD is not universal for cancer survivors or caregivers, but it is common. When researching PTSD, I came across the term “post-traumatic growth,” and it felt like a lightbulb switched inside of me. It spoke to the human capacity for hope and resilience that I had been searching for when I came across Viktor Frankl’s work.

Resilience vs. Post-Traumatic Growth

Something that I have learned is that there is a difference between resilience and post-traumatic growth.

Resilience is what is demonstrated when a person is able to get back to their routine functioning after the traumatic event. Post traumatic growth is the next level up: when a person is able to create positive changes in their life following traumatic events (2).

Like PTSD, it is not universal, and so it shouldn’t be a standard requirement for someone who has gone through trauma.

Let me state this explicitly: growing from your trauma is not an expectation to put on yourself. It is enough that you have continued to be here, and be present.

If the term post-traumatic growth brings you hope, then great! If it puts pressure on you to make meaning from an objective crisis, I invite you to take a step back from the expectations that might come up with the concept.

Strategies for Cultivating Self-Care

Whether you have been recently diagnosed with cancer, a gene mutation, lost a loved one, or are suffering through the ramifications of COVID-19, here are some tips for fostering self-care:

1. Remind Yourself of Your Capacity

Look at previous hardships, and how you were able to go through them. Lots of times, those strategies can be used again or modified in your present-day struggles even if in a small degree. In moments where anxiety is consuming, be curious about the underlying emotion that is accompanying it, and when you felt that way in the past. Tell yourself what it is that you needed to hear in that past moment.

2. Practice Self-Compassion

Trauma, in its many forms, is not linear. Some seasons, days, or even moments, will bring you back to the pit. Be patient and gentle with yourself, especially in those moments. Treat yourself the way you would treat a close friend.

3. Find a Community

Finding people that have gone through similar struggles is incredibly liberating and empowering, like The Breasties or a similar support group. They will understand elements of your story unlike other loved ones in your life, and you can likely discuss topics with them that you wouldn’t otherwise be comfortable discussing with close friends and family.

4. Seek Out a Good Therapist

Sorting through trauma is an incredibly vulnerable and often painful process. Having an objective, empathic, and trained individual walk with you through your pain will bring about insight and strength you don’t know you have.

A therapist with a speciality in trauma will likely say so in their bio. Otherwise, finding a therapist that practices DBT (Dialectical Behaviour Therapy), EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing), NET (Narrative Exposure Therapy), or TF-CBT (Trauma Focused Cognitive Behaviour Therapy) is a good start.

And remember...

It is not a requirement to grow from your trauma: surviving your trauma is enough.

If someone is able to grow and better themselves from it, more power to them, but it is not a benchmark of one’s worth. You are enough, now, in this moment, wherever you are at. You are enough.

Reading Recommendations:

- The Post-Traumatic Growth Guidebook, by Dr. Arielle Schwartz This author is a complex PTSD researcher, and explores the mind-body connection in trauma. This book also acts as a workbook that encourages self-reflection and journaling.

- Self-Compassion: The Proven Power of being Kind to Yourself, by Dr. Kristen Neff Dr. Neff is the leading researcher on self-compassion, and her website also offers workshops, videos, articles, and tips for fostering self-compassion.

- The Year of Magical Thinking, by Joan Didion One of the first chapters goes through the physiological and culture aspects of grief and loss, while the rest of the book is a memoir of when she lost her husband and daughter.

- Grief and Bereavement: What Psychiatrists Need to Know, by Sidney Zisook and Kahtherine Shear The authors discuss the different sorts of grief: acute grief, integrated grief, and complicated grief.

- Man’s Search for Meaning, by Viktor Frankl Frankl accounts for his time spent in the concentration camps during the Holocaust, as he observed the differences between how individuals coped. The latter half of the book discusses logotherapy and meaning-making that was created from Frankl’s experience.

Sources

- Horowitz M., Siegel B., Holen A., Bonanno G., Milbrath C., & Stinson C. (1997). Diagnostic criteria for complicated grief disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 154(7), 904–910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun, L. G., Tedeschi, R. G., Cann, A., & Hanks, E. A. (2010). Positive outcomes following bereavement: Paths to posttraumatic growth. Psychologica Belgica, 50(1-2), 125–143. https://doi.org/10.5334/pb-50-1-2-125