With a warm smile, the woman at the Cancer Institute reception desk told me I was welcome to use the family/patient room. I respectfully declined. I wasn’t a patient. She glanced at my hospital bracelet and nodded down the hall. I could go in anyway, she said.

The room was large, with several couches, different-sized tables, fake plants, and a coffee machine. I beelined to the coffee. While attempting to figure out the buttons, a woman wearing a ‘Cancer Institute’ name badge approached and asked me how I was doing. I responded that I was fine—outside of my battle with the Keurig.

She helped me make a hot cup of coffee, asking me who my oncologist was as I took my first sip. I told her that I didn’t have an oncologist. Then she, like the woman at the front desk, looked down at my medical ID bracelet with soft eyes.

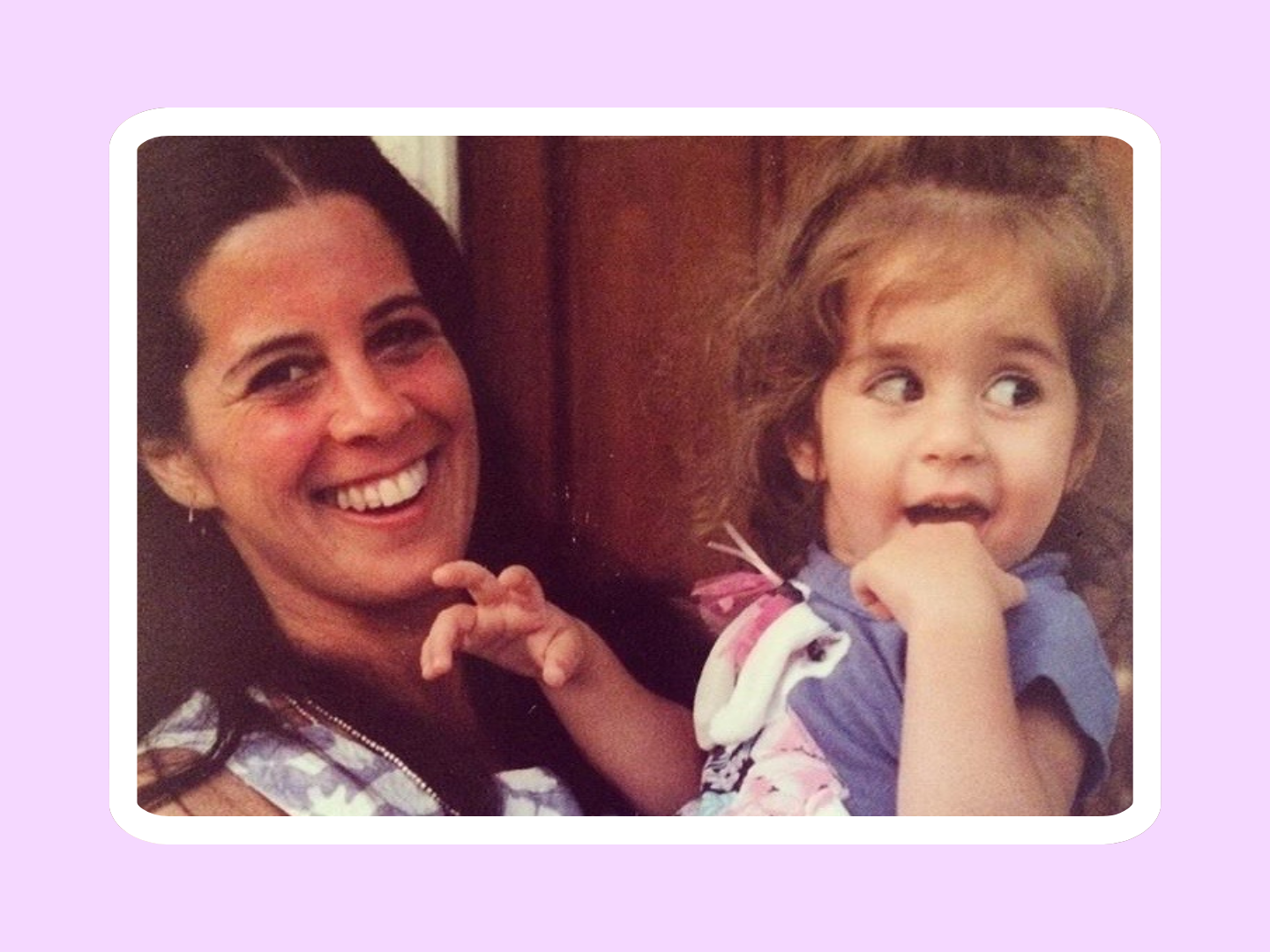

I had just completed my first round of breast imaging. I endured the loud thumping of the MRI machine, outstretched like Superwoman on my stomach. I had my breasts smushed between the mammography tables. I was 33 years old and was starting preventative screening, having recently found out that I carried the BRCA1 mutation, like my late Aunt Jan, who had passed away from ovarian cancer just months before.

Yet, I still didn’t see myself as a patient—just a visitor trapped in this weird world, sitting at a cancer center across the street from my sophomore-year college dorm.

Despite having no family history of breast cancer and my aunt being the only one in my family to have gynecologic cancer, doctors informed me that my chance of developing breast cancer was up to 80 percent and 30-40 percent for ovarian cancer over my lifetime.

Previvorship: Scanxiety and Limbo

And so it began. Countless doctors’ appointments, the introduction to ‘scanxiety,’ and over a half-dozen biopsies (all benign) in a 20-month period.

The life of a previvor. I existed in a state of anxious limbo. My friends and family often told me not to worry.

They couldn’t grasp the apprehension that trailed me. My Uncle Mark did, though. He had seen his beloved wife, my Aunt Jan, navigate the oncology floors of multiple hospitals. On one of our calls, I shared my fears.

”I know,” he said, “It’s like you have a piano constantly dangling over your head, kept up by a thin string.”

I moved back to my hometown of Tucson, Arizona, in spring 2020, right as the pandemic began. Being proactive, I asked local friends in the medical field who to see in Tucson for BRCA monitoring.

I was matched with a highly regarded breast surgeon and was thankful to have access to continued screening despite the barriers to medical care that Covid imposed.

Survivorship: Triple-Negative Breast Cancer

In July 2020, my MRI was slightly suspicious but labeled “probably benign.” A 6-month follow-up MRI was recommended. In October 2020, between scans, I felt a lump in the shower when doing a breast self-exam.

Six weeks later, I was told that the mass was cancer: triple-negative (TNBC), to be exact. I knew what TNBC was. The figurative string holding the piano up broke, and I was afraid. When the surgical oncologist said I would be starting chemo before the new year, I could barely breathe.

My tumor was nearly 5 cm (the size of a lime), grade 3, and I was deemed stage 2b.

I quickly went from being a previvor, weighed down by the frequent screening and anxiety of the looming possibility of a cancer diagnosis, and was now thrust into the world of treatment.

As a previvor, I had undergone mammograms, MRIs, and physical exams every 3 to 6 months for almost two years, following my doctors’ instructions to a tee. And now, overwhelmed and frightened, I was about to undergo 16 rounds of chemo, starting infusions shortly before my 36th birthday.

In addition to chemo, a double mastectomy, and reconstruction, in consultation with my gynecological surgical oncologist, I chose to undergo a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) to reduce my risk of ovarian cancer, due to my BRCA1 mutation. So, at 37, after already losing my breasts, I parted ways with my ovaries and fallopian tubes.

The Intersections of Previvors and Survivors

It’s been nearly four years since I found my lump. My long hair has grown back curlier than ever, and while my pant size has increased (thank you, surgical menopause) and I continue to use sticky scar cream, I relish that I am alive. Many of my friends dread our big ‘four-oh,’ but I eagerly await my 40th birthday—a milestone I wasn’t sure I would reach.

I am a previvor and a survivor.

I hope that when previvors begin surveillance for increased cancer risk, their fears and worries aren’t dismissed. I hope they see themselves as patients deserving of excellent medical care and support.

I hope they, as well as those around them, acknowledge the inherent difficulties of previvorship and the very valid feelings that emerge when faced with increased cancer risk, ongoing surveillance, and frequent mention of “cancer.”

Previvors and survivors matter, wherever you are on your journey, and so often our stories are intertwined.