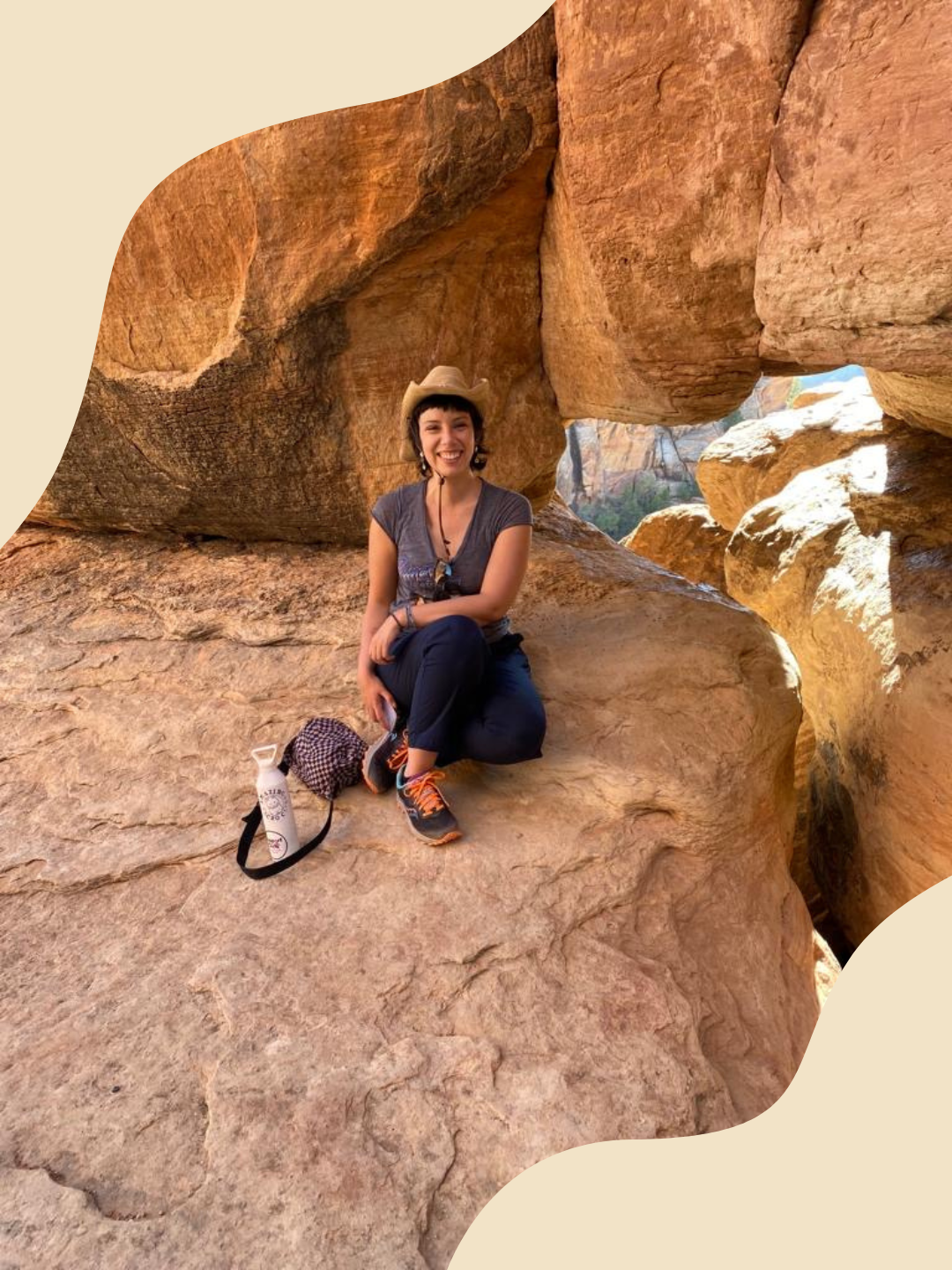

Ashley Dedmon never expected to pursue a doctoral degree.

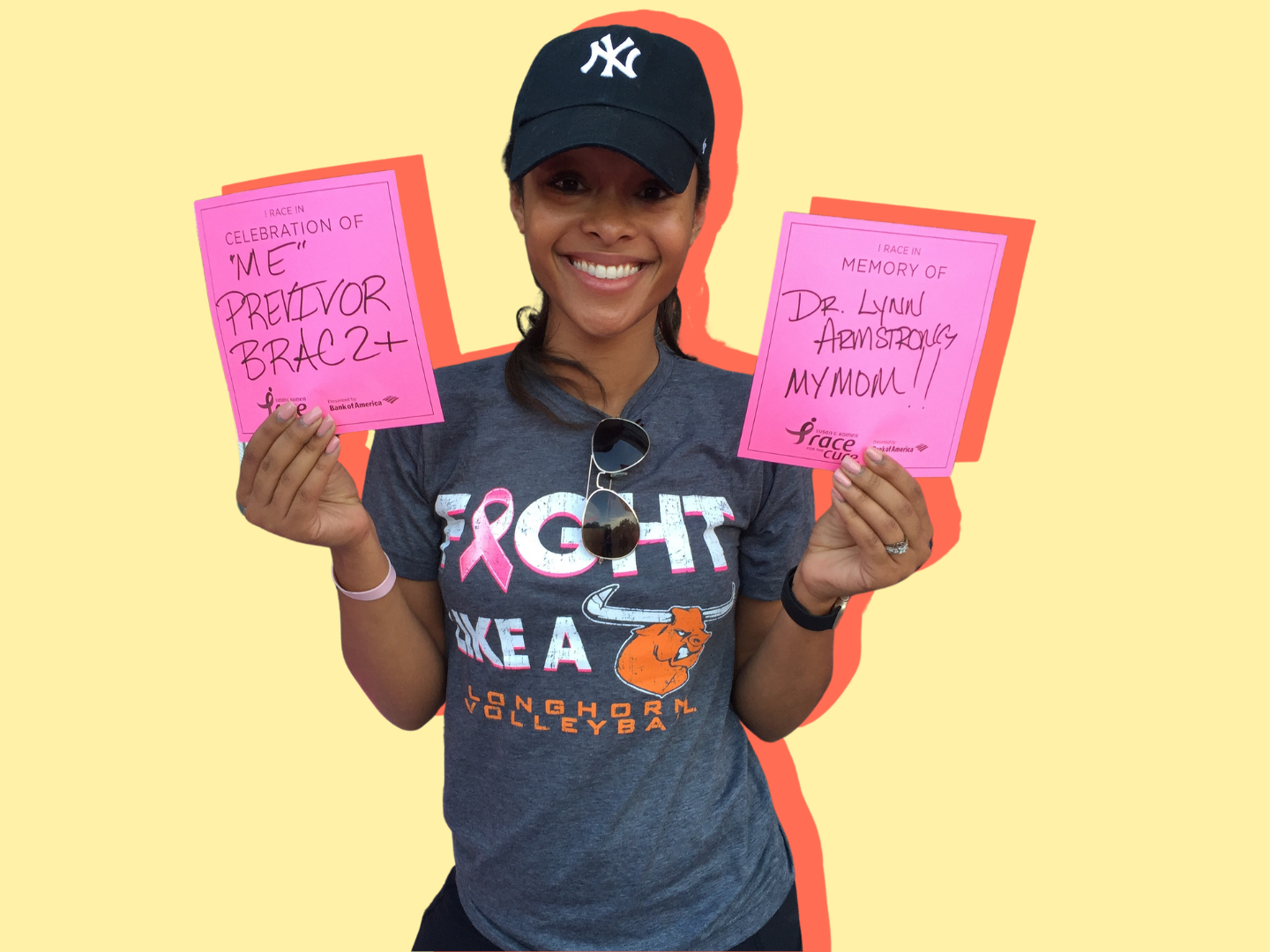

But after watching her mother receive a doctorate while undergoing treatment for stage 4 breast cancer and maintaining her work as a school principal, she says her life “took a different course.”

Now, she is on her way to a doctorate at the University of Texas Houston School of Public Health, undertaking research that is motivated by her culture, as a Black woman, and family, as a carrier of the BRCA2 genetic variant, which contributes to a 60 percent lifetime risk for developing breast cancer.

“When we look at the disparities today, Black women are 40 percent more likely to die from breast cancer,” says Dedmon. “We are diagnosed at later stages and with more aggressive forms of breast cancer—triple negative breast cancer being one of those aggressive forms which is also linked to BRCA2 mutation.”

That is why Dedmon says she feels it was important to see herself in her research.

“Historically, when we talk about research and the Black community, the narrative is not good.” Dedmon explains. “We know that historically, it was a process that was taken advantage of.”

One example is the story of Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman whose cervical cancer cells were hugely important in the development of modern cancer treatment and prevention strategies. But the research using Lacks’ cells was done without her or her family’s consent.

“I think it's being able to look at what's been done historically and acknowledging it, but also making sure that going forward, we conduct research in an ethical and appropriate way that's proper for all mankind.”

Seeing the Forest for The Trees

Public health is the study of how diseases emerge among populations and the actions we can take to prevent them.

This often includes the study of social determinants of health, which Dedmon describes as “non-medical drivers of health.”

Dedmon offers transportation, child care, and food security as examples. If a person is unable to find someone to care for their child, it can impact their ability to make it to their mammogram to stay on top of cancer screenings. Or, someone who lives in a rural area may have trouble getting to a comprehensive cancer center that could provide them with the treatment they need, ultimately affecting their disease outcomes.

“Those are all the factors that play a critical role,” she says.

Epigenetics is how those outside factors influence our genes and cause changes. In the field of public health, Dedmon explains, epigenetics provides “ another critical layer of how we can begin to address health disparities and begin to advance health equity.”

For example, Dedmon explains that ”the psychological stressors that Black women have endured historically, such as racism,” add to the previously mentioned stressors to increase the allostatic load or the cumulative impact of chronic stress on the body.

“All of those things play a part in the epigenetic changes that [contribute] the development and the progression of something like breast cancer.”

Better Representation, Better Outcomes

Having this information can be critical in many ways.

Dedmon also says that having a diverse set of research to draw from allows healthcare providers to tailor a patient’s treatment according to what they know about how a person with that racial background responds to treatment.

But Dedmon says it also dares us to go a step further. “One thing I'm being challenged with in my doctoral program is: Do we need to do away with race-based interventions and just treat everyone in an equitable way and give everyone the individualized care that they need?”

On a broader level, Dedmon says we can get there by advocating for policies that expand access to genetic counseling and testing, preventive screening, and personalized care.

“It's continuing to build communities and coalitions and partnerships to push for better representation in clinical trials and improving access to preventive care.”

In addition to policy, Dedmon says it's important to further educate others about risk factors—such as breast density and family history—on top of the importance of early detection and finding support in community.

“People can learn from other people and I think being able to have educational resources that are tailored to the unique needs of Black women and that understand that cultural sensitivity is so important.”

“And then finally, supporting research,” she says. “There are a lot of great organizations focused on research."

"It's continuing to allow ourselves to be open, to learn, unlearn, and relearn from the research and the community, and then go out and be allies with whatever privilege we may have. To be the voice at the table, to get comfortable with being uncomfortable, and be open to having hard conversations”